A little background

During May and for about a month we run our Team Lego initiative. You can read more about it here but the general idea was simple: create a new team that would be composed exclusively of entry level developers, preferably without any prior experience. We wanted to do this in order to tap into the pool of inexperienced developers in order to increase our engineering department headcount and at the same time provide opportunities for new developers. This post provides some numbers, looks into some of the online test questions and includes some reflections on the whole process.

Expectations and reality

We thought that our initial expectations were high but they turned out to be modest after all. We expected to receive about 200 applications out of which we would select about 70% for an online screening test. The test was a series of multiple choice questions and simple programming exercises, crafted out in such a way to yield a normal distribution of results. The highest test score to be attained was 1000 points and we set a pass score of 650 points for the online test. With a few exceptions, almost everyone that would score above that threshold would be invited for an online interview and we expected that we would have 30-35 candidates that would make it. Of those, we were planning to select the top 15% (or the top 2.5% overall) and give them a job offer.

The reality turned out to be very different in some respects. We had 257 applications, slightly more than those we anticipated. However, the attrition rate at the first stage was not 30% but 14.7% or 38 candidates. The quality of the applicants was significantly better than what we expected and we ended up giving out 219 online tests, 79 more than what we thought we would. Of the 219 candidates that took the online test, about 65% were disqualified based on the results (more on this later). That left us with 75 people that had a good entry level CV and had passed the online test.

Before we started interviewing these people, I thought to myself that we could simply be strict and instead of picking the top 15% of the people that reached this stage, we would just raise the bar and pick the top 6.6% by selecting the strongest candidates. After just a few interviews, it became clear that a lot of the applicants could be strong or very strong entry level developers. We had a discussion in the company about the opportunity that was before us. We could stick to our original plan and easily end up with a 5-person team. That would be the path of least friction for us, both in terms of the capacity we would be devoting to mentor the new people and help them grow and also in terms of financial investment.

However, any company that has been hiring software engineers for more than a year can tell you that it can be a frustrating exercise. There is great demand for software engineers, so companies compete intensely for the people that are out there. Also important is the fact that hiring is an activity without a predictable pipeline. You might be lucky enough to find and hire people at a normal pace but more often than not new developers arrive in totally unpredictable clusters, which can make the onboarding process more chaotic and tiring.

We decided to make the best of this opportunity and hire as many people as we could. We accepted the increased financial investment that we would have to make but most importantly we acknowledged the fact that our day-to-day life would be much more disrupted for some time. Currently our engineering team is 35 people split into 8 teams. Growing the headcount of the team by 20-30% each year is an activity that can be somewhat streamlined. But growing the same team by 50% within a few months is certain to upset everything, from our existing structure that would require changes, to the stress applied to the people responsible for mentoring the new arrivals, to the throughput of the entire engineering department that would certainly get worse before it gets better.

Tuckman’s five stages of team development

Tuckman’s five stages of team development

Essentially we would be going through minor or major stages of team forming. Regardless, we decided to pick the maximum number of good candidates that we believed we could onboard, even at the expense of a multi-month slow down of the development process. After all interviews concluded, we evaluated every candidate and took whatever aptitude they had into consideration. We ended up making 4 times more proposals than we expected to do, bringing in the team 20 new entry level developers.

The online test

During normal hiring we give a coding challenge to applicants. The contents vary depending on the specialty we are looking for, but generally the challenges require 6-10 hours of work to complete and can be solved in many different ways. These code challenges require significant effort from our side to evaluate the responses and, more importantly, assume that candidates have at least minimal experience with production applications. We needed a more standardized approach because of the number of applicants we expected but also because we knew Team Lego candidates would have absolutely no real world experience. We decided to use an online test platform and create a test that would focus on the basics.

What are the basics and what we were looking for? We expected that good entry level developers should be able to exhibit the following skills:

- Understand the basics of computer science topics such as data structures, complexity theory and distributed programming.

- Have minimal knowledge of how a web page or application works.

- Most importantly, we wanted to know that an applicant could solve basic programming exercises in a language using C-like syntax (in our case we selected Java) and in any other programming language of their choice.

We decided that our online test would contain both multiple choice questions and programming exercises, with 40% of the score derived from the multiple choice questions and 60% of the score derived from the programming exercises.

We wanted to ensure that the online test was neither too easy nor too hard. We needed to have enough questions that we could weed out candidates that did not have a good grasp of the fundamentals. We also needed to allow candidates a fair chance of scoring well enough to pass the 65% base score - on the other hand we also required that it would not be easy to ace the test.

We ended up creating 12 multiple choice questions and 3 programming exercises of varying difficulty. Two programming exercises were in Java and one programming exercise could be solved in a number of different languages. Although the online test platform we selected allowed us to prevent candidates from browsing online resources for the duration of the test, we did not use that option because we did not require candidates to have things like language syntax memorized, just as we do not. The real difficulty of the online test was that it would have to be completed within 90 minutes. This proved to be a good test of the time management skills of candidates.

The candidates received an email inviting them to the online test. The email described the nature of the online test and urged candidates to find a quiet place for 90 minutes when taking the test and to use the test platform’s sandbox functionality. The sandbox allowed the candidate to take a quick mock test and get comfortable with the platform before tackling the online test itself.

The online test platform provided several insights and allowed us to examine the actions of the candidates when they were using it. After seeing the submission results of the candidates, there were some common themes that we observed:

- Almost half of the candidates either did not go into the sandbox or if they did, they spent less than 5 minutes in it.

- Many candidates were overwhelmed by the test and started going through it in an undisciplined manner. There were several candidates that devoted an inordinate amount of time to specific questions and ended up running out of time.

- Some candidates finished early but did not check the results of the test cases of the programming exercises.

- Amazingly, a few candidates finished very early but did not even try some programming exercises because they did not know the language they were in.

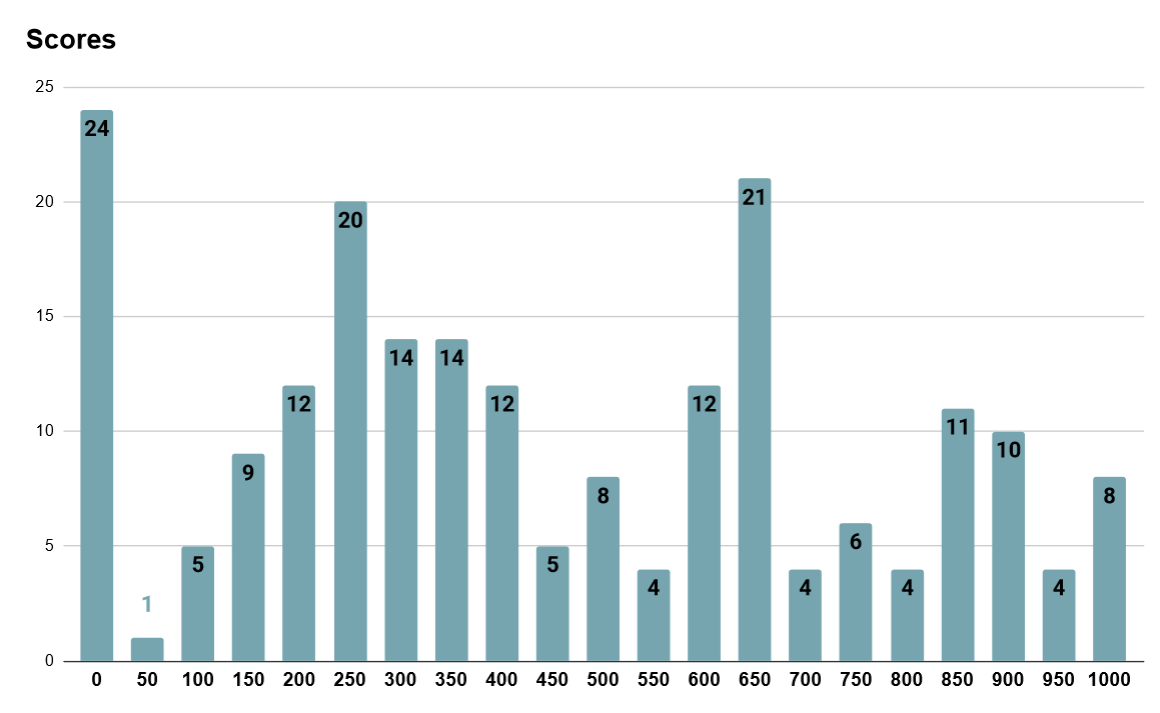

The final scores grouped in units of 50 looked like this:

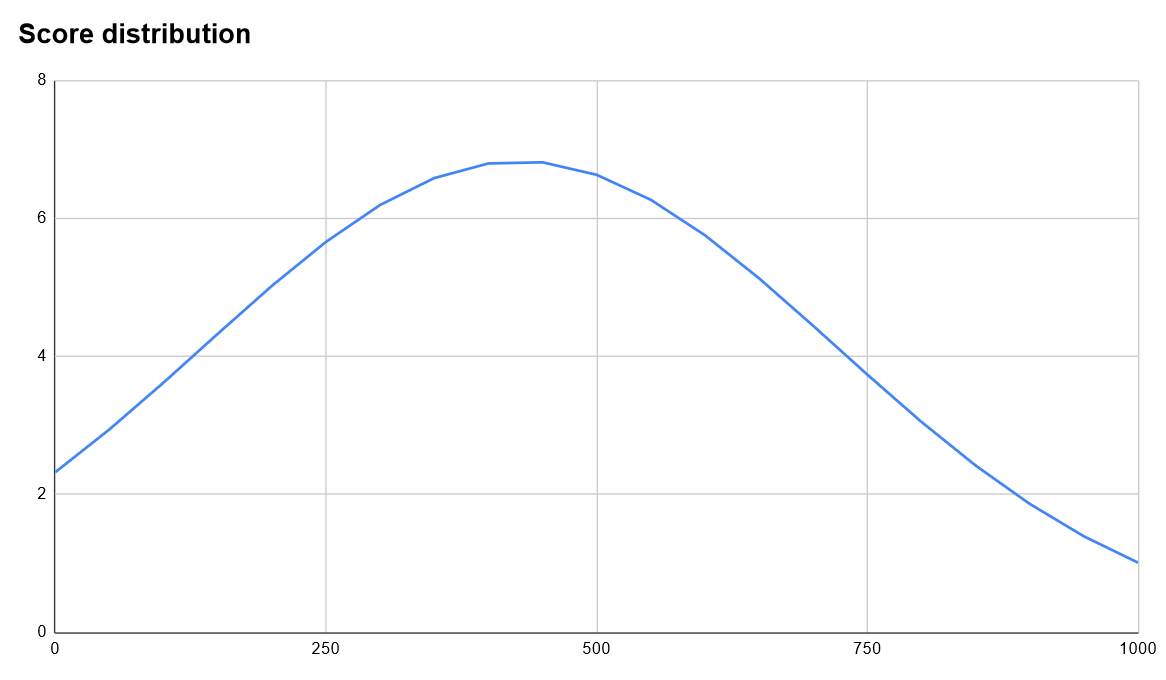

The graph shows that 21 submissions were rated between 650 and 699 and that 11 submissions were rated between 850 and 899. The distribution of scores looked like this:

The graph shows that 21 submissions were rated between 650 and 699 and that 11 submissions were rated between 850 and 899. The distribution of scores looked like this:

A few highlited questions

One of the easiest complexity questions involved linked lists. Here it is:

A linked list is a structure in which each element contains some data and a pointer to the next element. Given that you have a pointer to the first element of a list that contains N elements, you want to implement two operations: A pop operation will remove the first item from the list and an append operation will add a new element at the end of the list. Which of the following statements is true regarding the complexity of these operations?

- Both operations are O(1)

- Both operations are O(N)

- Pop is O(1) and Append is O(N)

- Pop is O(N) and Append is O(1)

To answer this question one would need to know what O notation is and what a linked list is, which is a very basic data structure. Although in high level languages developers typically do not bother themselves with the inner workings of constructs implemented in the language they use, it is imperative to know how they work in order to select the most appropriate construct for the job. In this specific case, having the head pointer to the list means that you can perform a Pop with a single operation every time - you just change the value of head to the next pointer of the first element and discard the data of the first node, so this operation is O(1). To append a node, however, you need to traverse the list to find the final node. If the list contains N elements, you need to perform N traversals and therefore the operation is O(N). Obviously actual implementations of a linked list might very well be optimized to keep a pointer to the last element in order to speed up an append operation but this was not the case stated in the exercise. About half of the candidates got this question wrong.

Another question asked where a javascript referenced in an html file would be executed. Specifically the question was this one:

A web server serves a valid and error-free html file that includes the following statement in its <head> declaration:

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/3.1.1/jquery.min.js"></script>Where will the referenced Javascript code be executed?

- On the server located at ajax.googleapis.com

- On the server that served the html file

- On the client (e.g web browser)

- No code will be executed

Surprisingly enough, a significant percentage of the candidates did not select “On the client” but selected one of the other choices. This told us that these candidates were either in a great hurry and selected the wrong response or that they had a very limited understanding of how client side Javascript works.

There was also a question on binary operations, specifically what is the value of 01 ORed with 11. The possible answers were 00, 01, 10, 11 and 100 with 11 being the correct answer. This particular question caused a few raised eyebrows internally when we were creating the online test. I heard the argument being made from more than one of our developers that they might not be able to answer this question without refreshing their knowledge on what an OR operation does, because they are too removed from these basics. Although that might be understandable, I was of the opinion that entry level developers fresh out of computer science or related curriculums should have this knowledge readily available in their minds. And bits and bytes turn out to be useful in all sorts of places even when using high level languages, so this question was included. It turned out that many candidates could not answer this question correctly.

One of the programming exercises was the robotic packages classifier. In that, a robotic arm was called to classify packages according to their dimensions and weight to three categories. If a package was bulky if its volume was greater than 1,000,000 cm3 or if one its dimensions was greater or equal to 150cm. A package was also heavy if its mass was greater or equal to 20kg. A package was classified as rejected if they were both heavy and bulky, special if they were either heavy or bulky and standard if they were neither heavy nor bulky. Candidates were asked to change this method:

public static String solve(int width, int height, int length, int mass) {

// Write your code here

// To debug: System.err.println("Debug messages...");

return “”;

}Here is one of the correct responses we received:

public static String solve(int width, int height, int length, int mass) {

if( ((width * height * length >= 1000000) || (width>=150 || height>=150 || length>=150)) && (mass>=20)) {

return "REJECTED";

} else if ((width * height * length >= 1000000) || (width>=150 || height>=150 || length>=150) || (mass>=20)) {

return "SPECIAL";

}

return "STANDARD";

}Although it can certainly be further simplified, the code is to the point and easy to understand. I was glad to see that the majority of the submissions successfully provided a correct solution to this problem.

Final thoughts

It may not be obvious, but running the Team Lego initiative was an exercise that required a great deal of effort from our side in order to ensure that it was communicated effectively and executed correctly. Initially we ourselves also had doubts about the number of people that would follow up the initiative and also feared that we might not be able to find high-quality candidates. A few of our outside collaborators that heard about the initiative were also sceptical and voiced their opinion that we would not be able to successfully source candidates or that a lot of people from unrelated disciplines would apply.

It turned out that our fears were unfounded and that we were lucky enough to find many people that have great potential. Now the difficult task of onboarding them to our team and mentoring them is ahead of us but with explicit and clear management buy-in we are looking forward to doing this. We are doubtlessly going to make mistakes and we’ll have to correct them. We will surely have a busy time to successfully expand the engineering team so quickly. And we will definitely need to expand teams other than engineering as well, something that will become evident once our new colleagues start making contributions to the production code and the engineering team throughput starts growing noticeably.

Regardless of the effort that we’ll need to devote to ensure that our new colleagues become productive as quickly as humanly possible, we were encouraged by the fact that we met so many young people with great potential. We expect that, all things being equal, we will be running the Team Lego initiative again in 2022.